Drones buzz like bees, hover like hummingbirds, and

accelerate like race cars. Besides being used for play, drones, properly known

as unmanned aircraft systems (UAS), have quickly become vital pieces of

technology for both private and public organizations. First responder organizations

rely more and more on them to enhance their response capabilities and better

execute their missions. But how can first responders be sure the drones they

are buying meet their specific mission needs?

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and

Technology Directorate (S&T) can help.

In November 2019, S&T’s National Urban Security

Technology Laboratory (NUSTL) assessed small, commercially available drones for

priority needs of first responders through its First Responder Robotic

Operations System Test (FRROST) program. The needs were identified by the

S&T First Responder Resource Group (FRRG), a volunteer working group of

experienced emergency response and preparedness professionals from across the

U.S. who guide research and development efforts. The assessment was performed

under realistic field conditions at Camp Shelby Joint Forces Training Center in

Mississippi.

“We are focused on the first responder community – fire,

police, and emergency management departments – and we are assessing small UAS,”

said Cecilia Murtagh, FRROST Project Manager. “They are much cheaper than

manned aircraft, which makes them an ideal tool for response agencies.”

S&T initiated the FRROST program in 2018 to help the

first responder community evaluate drones in real-world field conditions under

simulated scenarios to inform their purchases. FRROST is modeled after

S&T’s System Assessment and Validation for Emergency Responders (SAVER)

Program, managed by NUSTL. It assists emergency responders in making procurement

decisions by producing reports based on objective assessments and validations

of commercially available technology. FRROST focuses on drone technology and

uses assessment methods developed by the National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST).

In June 2018, a focus group of first responders,

experienced in piloting drones for different missions, convened to provide

evaluation criteria for the FRROST assessment. The focus group selected several

drones to be tested and evaluated in realistic field conditions.

Becoming the ‘right hand’ of first responder

organizations

D.J. Smith from Virginia State Police operates the remote

control of a Falcon 8+ drone by Intel. Small drones offer tremendous potential

for emergency response missions. Thanks to recent technology advances, they

have become more effective, more affordable and easier to fly. They can not

only keep responders safer, but also provide opportunities for missions

impossible for manned aircraft, such as exploring inside buildings and tunnels.

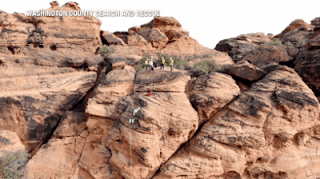

“Drones are a force multiplier for first responders,”

said Murtagh. “It gives them eyes on a situation quickly with generally less

manpower; for example, you could fly a drone over diverse terrain or wide areas

and try to find a lost hiker, which would be labor intensive for field teams.”

Law enforcement responders use drones for tactical

operations, building searches, traffic crash investigation, pursuit, and more.

For example, the Plano, Texas Police Department used a drone to look for an

armed suspect hidden in an apartment complex.

“The subject was actually firing rounds out of the

apartment, so we couldn't get close enough to look in,” said Lieutenant Glenn

Cavin of the Plano Police Department. “The UAS was able to look through the

window and provide intelligence.”

After floods, emergency managers use drones to survey

actual damage, so they send help where it is actually needed without risking

responders’ lives.

“We have launched our drone to find a missing older

adult,” said Randy Frank, Director of Marion County, Kansas Emergency Management.

Small counties like Marion use the same drones for multiple missions. “Drone

use is only limited to your imagination.”

Large counties like Orange County, California, need

different drones for their various terrains, including metro city, wildland-urban

boundary, harbors and more.

Tom Haus from the Los Angeles City Fire Department sets

up video to capture the operator interface while the participants fly the NIST

Test Methods.“During a brush fire, a drone can map out where the hot spots are,

thus helping the firefighters to put that hot area out,” said Frank Granados,

Firefighter Paramedic at the Orange County Fire Authority, CA.

First responders assessed drones at Camp Shelby

In November 2019, nine first responder drone pilots from

across the U.S., some of whom are quoted in this article, assessed four small

drones in fields and mock urban settings at Camp Shelby. The drones weighed

between 1.9 and 13.5 pounds. The pilots, with law enforcement, firefighting and

emergency management backgrounds, participated in three different search and

rescue scenarios: lost hiker (in an isolated field), post-flood disaster (in

the urban setting and an adjacent field) and a twilight scenario (in the urban

setting). The drones demonstrated different capabilities and participants

provided feedback to NUSTL after taking turns flying them. NUSTL coordinated

with NIST for this testing event, using a test course that NIST developed for

drone assessment and pilot training and testing.

“All participants are getting an opportunity to run the

drones through those standard test lanes to see how they match up against what

they would like to see in a mission ready, small unmanned aerial system,” said

Captain Tom Haus of the Los Angeles Fire Department, who assisted NIST with FRROST’s

standard testing and scenarios.

Falcon 8+ drone hovers over a car with a cluster of NIST

buckets to look for ‘stranded flood victims,’ as part of the FRROST search and

rescue scenario.Wooden stands stood in a wide field next to the urban setting at

Camp Shelby. Clusters of white two-gallon buckets like giant bell-shaped

blossoms adorned the stands. Other clusters were attached to windows, roofs,

and even a car. Inside each bucket on the bottom was a sticker with a letter

surrounded by a circle. Such stickers could be seen on other parts of the

buckets and poles. The drones had to hover over each bucket, like honeybees

over a flower, and take accurate pictures.

“These visual acuity tests, just like the eye charts at

the eye doctor, are designed to allow the operator to align his/her small

unmanned aerial system with that bucket” said Haus. “If you are not aligned,

the bucket itself keeps you from seeing into the bottom.”

Participants assessed how well the drones could be

stabilized, how easily they could be flown, and how well their payloads

functioned. Payloads included 30x zoom cameras for distant visualization and

thermal cameras for twilight and night.

During the twilight testing, drones demonstrated their

thermal imaging cameras and participants watched on a monitor what the drone

was ‘seeing.’ One of the pilots moved the drone vertically, hovered it over the

car, a roof and in front of a window, all with clusters of buckets. This

simulated how a drone could be operated to look for survivors after an

emergency or disaster, such as a hurricane.

NUSTL representative Cody Bronnenberg (right) records

feedback from UAS Trainer Coordinator Christopher Stockhowe (left) from the

Virginia Beach Fire Department after he flew the EVO drone by Autel Robotics.FRROST

took place over four days, with a different drone assessed each day. A large

drone with a 42-megapixel camera and an infrared camera was tested during the

last day. It was designed for professional inspection and surveying of bridges

and other areas. The first responder evaluators determined that it could be

paired together with a smaller, faster drone. In this scenario, the evaluators

used the large drone for overall incident awareness and then used a smaller

drone for closer inspection.

Future outlook

The feedback provided by participants in the FRROST event

will be documented in a final assessment report and shared nationally with the

first responder community. NUSTL’s report will provide unbiased results that

can help first responder organizations with their procurement decisions.

Moving forward, another S&T project called Joint

Unmanned Systems Testing in Collaborative Environment, or JUSTICE, assesses

drones and sensors for the Homeland Security Enterprise. JUSTICE is managed by

the S&T Air Based Technologies Program and a team of experts from the

Mississippi State University Raspet Flight Research Laboratory.

“Putting the drone in your hand, running it through its

paces, seeing how it performs in a real scenario helps me determine if that's

going to fit our mission and save us money,” said D.J. Smith, Technical

Surveillance Agent with the Virginia State Police. “That’s critical for us.”